Orchestral Speech: A technique for when you really need to be fluent.

By Paul Brocklehurst PhD. (Revised edition November 2023)

The Stammering Self-Empowerment Programme www.stammeringresearch.org/

click here for a printable .pdf version of this article

Introduction

If you are a person who stammers, you will know that there are times when you really need to be fluent. Despite all that we are taught about the importance of non-avoidance – of not avoiding blocks when they arise – there are nevertheless times when it really is important not to block and where we need to be able to get a message across quickly and fluently. If we fail to do so, we may miss an important window of opportunity, or we may fail to avert a serious accident. Also, an increasing number of companies use speech-recognition software to process their telephone calls. If you block, the software will not recognize your words. At such times, block modification techniques do not help. Orchestral Speech is for times like these.

Essentially, Orchestral Speech is a fluency-enhancing technique that prevents you from getting stuck and prevents you from producing any overt symptoms of stammering. It fits into the broader category of “fluency shaping” techniques and, as such, has much in common with some of the more traditional fluency-shaping techniques such as “syllable-timed speech” and “prolonged speech”, and indeed, it also has much in common with singing.

Orchestral Speech alone will not enable you to overcome the fear of blocking. So, although Orchestral Speech is effective in the short-term, if used in isolation it is not a long-term solution to stammering and should not be thought of as such. I think it is important to emphasize this fact because, in my experience, clients are often tempted to start to employ it as their only technique and, as a result, they never learn to employ the block-modification techniques (such as “the Jump”) which really would have the long-term effect of reducing their fear of blocking and reducing stammering itself. So, I’m sounding a note of caution here. Orchestral Speech (and other fluency-shaping techniques) are highly valuable – and indeed necessary in some situations. But they can become a serious hindrance to your long-term progress if you rely on them exclusively and use them too often.

How does Orchestral Speech work?

To answer this question, it is useful to consider Orchestral Speech together with some other closely related fluency-shaping methods such as “Syllable-timed speech” (speaking in time to a metronome); Choral speech (speaking together with a group of others); Shadowing (a language-learning technique that involves repeating immediately what somebody else has just said); and singing.

Orchestral Speech changes your focus of attention.

Essentially, what the above-mentioned fluency-shaping methods all have in common is that they make you give higher priority to the forward flow of speech than to the phonetic accuracy of each sound. This change of priorities is all-important because, as a general rule, people tend only to stammer when they are concerned that what they are about to say may not come out in the way they want it to come out and may not sound good enough or clear enough for the listener to understand. This concern triggers a physiological response that, for one reason or another, makes it harder to initiate articulation of the particular sounds they are concerned about[1].

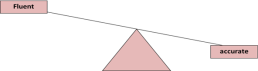

The fluency – accuracy trade-off

An easy way to understand how Orchestral Speech works is in terms of the “Fluency – Accuracy Trade-off”. Essentially, because the speech production mechanisms of people who stammer are slightly error-prone, when we try to speak, the sounds that come out of our mouths do not always correspond exactly to the sounds we intend to say – even when we are not actually stammering. Because of this, we have a tendency to focus too strongly on the sounds we are making while we speak and on avoiding potential speech errors, especially in situations where we consider it important to speak clearly and accurately. The problem with this is that, the more we focus on pronouncing each word correctly, the less fluent our speech becomes. Because our language and speech production systems are error-prone, if we try too hard to avoid or eliminate our speech errors, our speech inevitably becomes dysfluent. So, effectively we have to make a choice… we can either give priority to maintaining the forward flow (i.e., the fluency) of what we want to say – in which case our speech will contain somewhat more speech-errors than that of normally fluent speakers, or otherwise we can give priority to speaking accurately – i.e., to pronouncing each word correctly, in which case our speech will be relatively dysfluent (compared to that of normally-fluent speakers). Of course, it would be nice if we could speak both fluently and accurately just like most non-stammerers can, but because of the underlying weaknesses in our language and speech production systems, this is not always possible. The unavoidable reality is that if we give priority to fluency, we will tend to make more speech errors and the sounds that come out might not coincide with exactly what we intended, whereas if we give priority to making sure each word comes out exactly in the way we want, we will be more disfluent. Most of the time, most people who stutter focus more strongly on pronouncing each word correctly than on maintaining the forward flow of their speech. In other words, they tend to prioritise accuracy above fluency. In contrast, when using Orchestral Speech, effectively we are choosing to prioritise fluency above accuracy.

The fluency-accuracy trade-off: If we try to speak fluently our speech will come out less accurately. If we try to say each sound accurately, our speech will come out less fluently.

Challenging two underlying beliefs

The fact that people who stammer habitually focus more strongly on getting their words out accurately rather than just on maintaining the flow probably reflects an ingrained underlying belief that “If I only focus on maintaining the forward flow, my speech will not come out accurately enough for people to understand me”. In fact, this belief is often wrong, because, more often than not, when people who stammer do start focussing just on maintaining the forward flow, their listeners generally understand them much better than they expected. However, this belief is nevertheless extremely tenacious. It is usually also accompanied by another false belief… “If I try as hard as I can to speak as clearly and accurately as possible, people will understand me better”. In fact, the harder we try to speak clearly and accurately, the more disfluent we are likely to become and the more difficult it will be for people to understand us. So, in order to employ Orchestral Speech, we need to take the risk, ignore our prior beliefs (and our intuitive feelings) and just focus on maintaining the forward flow of speech and see what happens.

How to employ Orchestral Speech

Orchestral speech works best when uttering phrases that contain several syllables and when the subject-matter is relatively simple. It is harder to use with single syllable utterances and when discussing topics that require a lot of thought (I’ll say more about this later).

In order to successfully employ Orchestral Speech during an utterance, perhaps the most important thing is to cultivate the right mindset before you start to speak. Essentially, you have to make a determined and firm decision that you will focus entirely on maintaining the forward flow of what you are about to say, and you will not pay attention to what your words sounds like. Then, when you start speaking, make sure you maintain the forward flow at a rate that is appropriate for the speaking situation. Do not slow down if you anticipate that you might stutter or pronounce something wrongly (and don’t speed up either). Just ignore such anticipations and carry on speaking at the appropriate speech rate regardless of such anticipations. The best analogy for this is to speak as though you are playing an instrument in an orchestra or singing in a choir. In such situations, when a player or singer makes a mistake, they simply have to keep going (Hence the name “Orchestral Speech”). With Orchestral Speech maintaining the forward flow is all-important. So, when using this technique, you must maintain an appropriate speech rate and forward flow at all costs, even if it means missing out some sounds or words entirely in order to keep up. And if you do make a mistake, do not slow down or stop. Just keep going as if nothing has happened, and if you block, never use force to push through the block. (If you use force to push through blocks, Orchestral Speech won’t work.) Instead, just abandon the word you are blocking on and restart on the word that you would be saying had you not blocked – just like you would do when reciting something in unison with other people. This may mean missing more than one word in order to keep up. When you speak using Orchestral Speech it may feel to you like you are speaking carelessly or clumsily – a little bit like how some people speak when they are drunk. If you feel like that, then you are probably doing it correctly! The reality is that most people who stammer try far too hard to speak well. To reduce the frequency of our blocks, we need to lower our speaking standards. We need to be more careless – or rather “carefree” – with our way of speaking. Paradoxically, the less effort we put into speaking the more fluently and naturally the words come out and the better people will be able to understand us.

How can I use Orchestral Speech for single syllable utterances?

Many of our utterances just consist of a single syllable or word. Obviously, this can be problematic for any method that focuses on rhythm or forward flow, so these single syllable utterances sometimes need a special approach. The secret is to establish a rhythm to adhere to before you try to say the word you want to say. There are many ways to do this: For example…

If someone asks you your name, you can count down three…two…one inside you head and then say it out loud at the “zero” moment,

three…two…one…“Paul”

Or you can take a short in-breath and then, without hesitating, immediately say it on the out-breath. Effectively, the in-breath acts as a timing-cue – equivalent to a metronome beat. For this method to work, its vital to be completely strict with the timing – such that the length of the inbreath should be identical to the time you take to say the word.

Inbreath…“Paul”

An alternative method is to embed the single-syllable word into a larger utterance. So, for example I could say “my name is Paul”. Doing so enables me to establish a rhythm out loud. This method can be particularly useful if the first attempt to say the word fails. However, it is important to only use this approach sparingly and be careful not to get into the habit of adding extra words. Of course, you can’t do this when speaking your name into speech-recognition software (although you can silently mouth the first three words before saying “Paul” out loud).

Whichever of these techniques you adopt, put very little effort into speaking the word you want to speak, and don’t use force to push the word out. If the technique doesn’t work and the word doesn’t come out, don’t keep trying. Give up immediately and find another way of getting the word (or the message) across. Spelling the word out – saying one letter at a time – is a good alternative. In which case, make sure to say the letters rhythmically – one letter per beat. If that doesn’t work, feel free to use any reasonable means to get the message across without the use of force, including word-substitution (if it’s possible), gesturing, or writing the word down. This may sound like avoidance, but it’s not, because you have tried (and failed) to say the word. There is no point continuing to try to do something that has not worked.

What if orchestral speech doesn’t stop you blocking?

If you find that your attempts at Orchestral Speech are consistently failing and you are still blocking too much, this suggests that you are not managing to focus your attention sufficiently strongly on maintaining the rhythm and speech-rate of the phrases you are trying to say, and instead you are still focussing on what your words sound like and worrying about whether or not the listener will understand what you say. If this is the case, it may help to temporarily limit your attempts to use Orchestral Speech to speaking situations that are relatively unchallenging – such as reading and making simple statements and requests – and use those easy speaking situations as opportunities to develop and strengthen your practice of Orchestral Speech, and then, once you have developed a stronger feeling for it to extend your use of it to more challenging situations – like conversations.

Whatever you do, whenever you try to use Orchestral Speech and find that you can’t get the words out, don’t keep trying. Give up immediately and be pragmatic about finding another way to convey whatever it is that you want to say. Feel free to substitute words, or spell words out where possible or write them down if necessary. The main thing is that you have tried to say the words you intended to say, so you haven’t avoided them.

And, as mentioned previously, if you find yourself blocking on a single word utterance, spelling the word out letter by letter, while maintaining a strict rhythm of one letter per beat often does the trick. If you don’t feel confident in your ability to use Orchestral speech in real-life speaking situations, then get some experience using it while reading. First of all, read to yourself, and then to other people. There are instructions on how to go about this in the Orchestral Speech module of the online course. It is helpful to record yourself while reading, so you can check how strictly you are adhering to the rhythm and maintaining an appropriate speech-rate. It may also help, initially, to use a metronome.

What if the listener doesn’t understand you?

Of course, when we employ Orchestral Speech, it is possible that sometimes our listeners won’t understand us. This is especially likely to happen when we make a lot of speech errors, and one or more important words don’t come out in the way we intend. This is especially likely to pose a problem with words (especially names) that are not commonly used or that are not in our native language and in situations where there are simply not enough contextual cues to help listeners correctly guess what the word we intended to say was.

If, when you get to the end of a phrase, if it is clear that the listener has not understood it, go back to the beginning of that phrase and say it again, in its entirety (avoid going back and repeating individual sounds or words). When you say it the second time round, try not to change anything of your original plan. Stick to it exactly if you can – word for word – and stick exactly to the rhythm and speech-rate you originally planned – even if it doesn’t seem like the best. Avoid the temptation to put any more effort in to saying it than you did the first time. In fact, if anything, you can put a little less effort into it. If you feel like the listener couldn’t hear you, resist the temptation to speak more loudly. If necessary, get a bit closer to the listener or, if possible, find a way of reducing the background noise.

On your second attempt, the chances of your listeners understanding you are greatly increased, even without trying harder and without changing anything. There are several reasons for this. First of all, they will be paying more attention. Secondly, they probably already heard and understood most of the words you said, so second time round they only really need to focus on the one or two words they failed to understand. Thirdly, even without making more effort, second time round, the words that come out of your mouth are likely to correspond more closely to what you intended to say than they did the first-time round – because you’ve already had some practice at saying them.

If, after a couple of attempts, Orchestral Speech does not result in the listener understanding what you are trying to say, then it is best to stop and resort instead to a different approach. In such situations it is important to be pragmatic and to feel free to use any means that are available – provided they do not traumatize you.[2] It is useful to remind yourself of what normally-fluent speakers do when they find themselves in similar situations, for example, when on holiday in a country where people do not speak the same language. Often the best options are to rephrase what you are trying to say, using different words; or spell the words out letter by letter; use gestures and point where appropriate; or simply to write down the word or words that have been misunderstood and show them to the listener. Or, if it has happened during a telephone call, you may need to call back later, get someone else to make the call for you, or resort to texting instead. Of course, it is disheartening when this happens, but importantly, because you have tried (more than once) to get the message across using Orchestral Speech and it hasn’t worked, you have not avoided the situation, so you will not have reinforced the tendency to avoid.

At the end of the day, it’s important to recognize that communication failure is also a common outcome even for people who do not stammer. Often, despite our best efforts, listeners can’t understand us – and that’s OK. Being overly idealistic in such situations does not help.

The Limitations of Orchestral Speech

It’s important to remember that Orchestral Speech is primarily a symptomatic remedy. Although, most of the time, you can successfully use it to avoid blocking; in the long-term it may not significantly reduce your fear of blocking. So, when you stop using it, you will likely find that the blocks and other stammering symptoms will return. In order to reduce the fear of blocking in a sustainable way, it is necessary to allow yourself to block and learn a way to quickly and easily get restarted when you do block. Our other technique – The Jump – is ideal for achieving this objective. So, once you have learned how to employ Orchestral Speech, it is important to then continue on and learn how to employ the Jump.

Orchestral Speech is easier to use in some situations than in others. It is particularly easy to use in situations where it is possible to pre-formulate what you want to say. So, for example, it is extremely easy to employ when reading aloud, or when reciting something you have already learned. It is also easy to employ when giving talks and it is very good for getting you started off when you first begin a conversation and for starting off telephone calls. However, it can be more difficult to use in ongoing conversational settings, because in such situations one cannot know in advance which direction the conversation will take, and consequently there is relatively little time to formulate appropriate responses and to find the appropriate words. And the less time one has to formulate one’s responses the more likely those responses are to contain a relatively large number of speech errors and “normal” dysfluencies, especially if the subject matter is complex. These speech errors and normal dysfluencies may tend to make it more difficult to maintain one’s focus on the forward flow.

Orchestral speech works best in spontaneous conversations if you have also learned how to employ the Jump. Then, if for some reason or other, while using Orchestral Speech, you lose the sense of rhythm and find yourself blocking, you can use the Jump to get restarted. Moreover, if you are already proficient at using the Jump, then it becomes easier to employ Orchestral Speech in conversational situations without feeling the need to formulate your phrases in advance. Thus, with the Jump as a back-up, it is indeed possible to successfully use orchestral speech “on the fly”– formulating and speaking simultaneously.

Finally, do bear in mind that ultimately, it is not a good idea to use Orchestral Speech any more than you really need to, and it’s not a good idea to adopt it as your only technique. It is better to restrict its use to the beginnings of conversations and for situations where you really need to be fluent. If over-used, Orchestral Speech may increase your tendency to avoid and to fear blocks, and it may not reduce your fear of listeners’ negative responses to your blocking. To reduce and ultimately eliminate such fears, you need to allow yourself to block and then use a reliable block modification technique such as The Jump to get quickly yourself restarted – so that your blocks do not elicit negative responses from your listeners.

Notes

[1] There are a number of possible explanations for why concern over speech accuracy may lead to the production of stuttered disfluencies. Two of the most recent theories are Vasić & Wijnen’s “Vicious Circle Hypothesis” and Brocklehurst, Lickley & Corley’s “Variable Release Threshold Hypothesis”

[2] To avoid the risk of being traumatized it is important not to resort to ways of speaking that involve the use of extreme force or that result in secondary symptoms that are likely to elicit negative responses and/or rejection from your listeners.

Orchestral Speech: A technique for when you really need to be fluent, by P. H. Brocklehurst is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be obtained on request. For details, see www.stammeringresearch.org/copyright.htm.